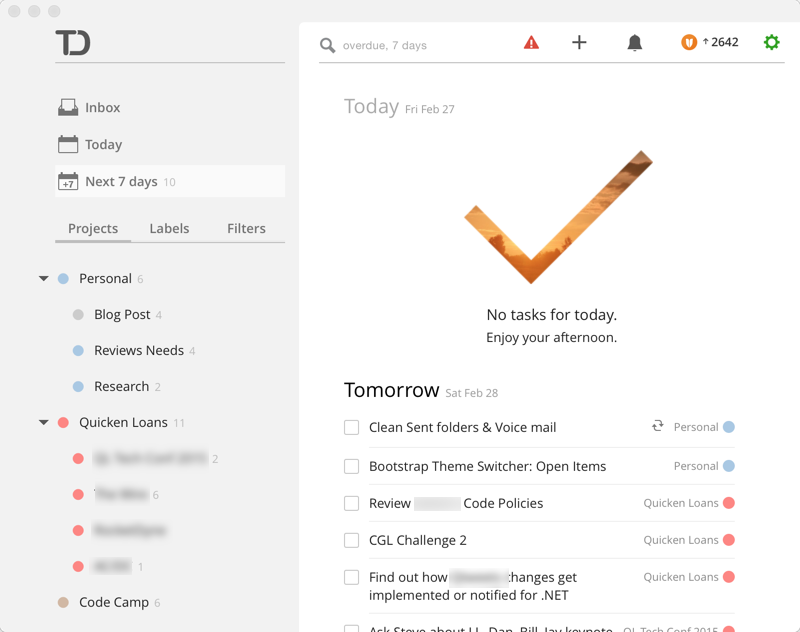

When you find yourself putting off a particularly big or difficult task, identify a very small first step you can take. The Zeigarnik Effect can also be used to our advantage. Make a plan for tomorrow before you end the work day so your unfinished tasks don’t linger in your mind after-hours.įind a small way to just get started. Create rituals for planning your day and week so your brain can trust you’re working on the right things at the right time and can worry about everything else later. Your system won’t work if your brain doesn’t trust that it’s accurate and up-to-date. Have a system for organizing and regularly reviewing your tasks. Keep a digital task manager like Todoist on your computer and phone, so you’ll always have it handy to jot down a new to-do. Instead of keeping tasks in your head, make a habit of writing them down as soon as they come to you. Research shows that simply making a plan to finish your incomplete tasks can snooze your brain’s automatic reminders. The good news is you don’t have to actually complete all of your tasks in order to feel mental relief from the Zeigarnik Effect. We need a way to find relief from the Zeigarnik Effect so we can mentally disconnect in our hours away from work. They intrude on our family dinners, our vacations, our weekends, and our sleep. Second, even if we manage to physically disconnect from work, the Zeigarnik Effect ensures that our unfinished tasks follow us home. One study found that people who were interrupted during a task performed worse on a subsequent task than those who were allowed to complete the first task before starting the second one. The problem when it comes to our productivity is two-fold:įirst, each incomplete task your brain reminds you about takes up a bit of your attention, splitting your focus and making it harder to concentrate on whatever you’re currently working on. At first glance the Zeigarnik Effect can seem like a handy adaptation: It’s good to remember the things we need to do, and it’s a positive thing to want to finish the things we start.

The Zeigarnik Effect refers to our tendency to remember incomplete or interrupted tasks better than completed ones. This observation gave rise to the study of what would become known as the Zeigarnik Effect. Yet, as soon as the bill was paid, the wait staff forgot completely what the orders were.

While dining out, she was impressed by the complex orders the wait staff was able to remember at one time. In the 1920s, Russian psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik observed an odd thing.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)